Kenneth Lapatin

(Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley) is Curator of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California. His research focuses on ancient Mediterranean

art, the history of collections, and forgery. He is the author of Luxus:

The Sumptuous Arts of Greece and Rome (Getty Publications, 2015).

The Getty Museum is one of the finest collections of classical art in the world. What is something about working there that most people would be surprised to hear?

Perhaps that my days are full of surprises. Each day I come to work, I think I am going to do one set of specific tasks, but those plans are frequently sidelined by something else, such as an email with an intriguing query from a scholar, or a bright young student writing a blog, or a discovery by one of my colleagues in our Conservation department that requires further research, or an eye-opening question from our graduate intern .... In short, what is so exciting to me about studying the ancient world is that, somewhat paradoxically, although it may seem over and done with, being some 2000 years old (plus or minus), there is still so much to learn. Our view of the past is constantly changing as we make new discoveries and ask new questions.

If, God forbid, you were at the Getty Museum when a fire or earthquake hit and you could make it out with only one piece from your collection, what would it be?

The Getty has very advanced

fire and seismic mitigation systems, so I have some confidence that the collection will survive anything but the gravest of disasters. But your real question might be what are my favorite objects. Well, I have many favorites, but I could not carry a large, heavy marble statue like the Hercules. Even the much lighter, hollow-cast bronze statue of a

Victorious Youth, one of our most important objects, would be difficult to heft.

One of my other favorites, which I can easily carry, but could not so quickly remove from its very secure display case in event of emergency, is a small amethyst engraved gem, which is signed by Dioskourides, who also carved the seal of the Emperor Augustus:

I am interested in the Kouros statue that is either from the 6th century or is a modern forgery. It is fascinating that scholars are still undecided about it. How many people would have the skill to create such a forgery, if that's what it is?

The Kouros remains a very interesting problem. Shortly before I came to the Getty,

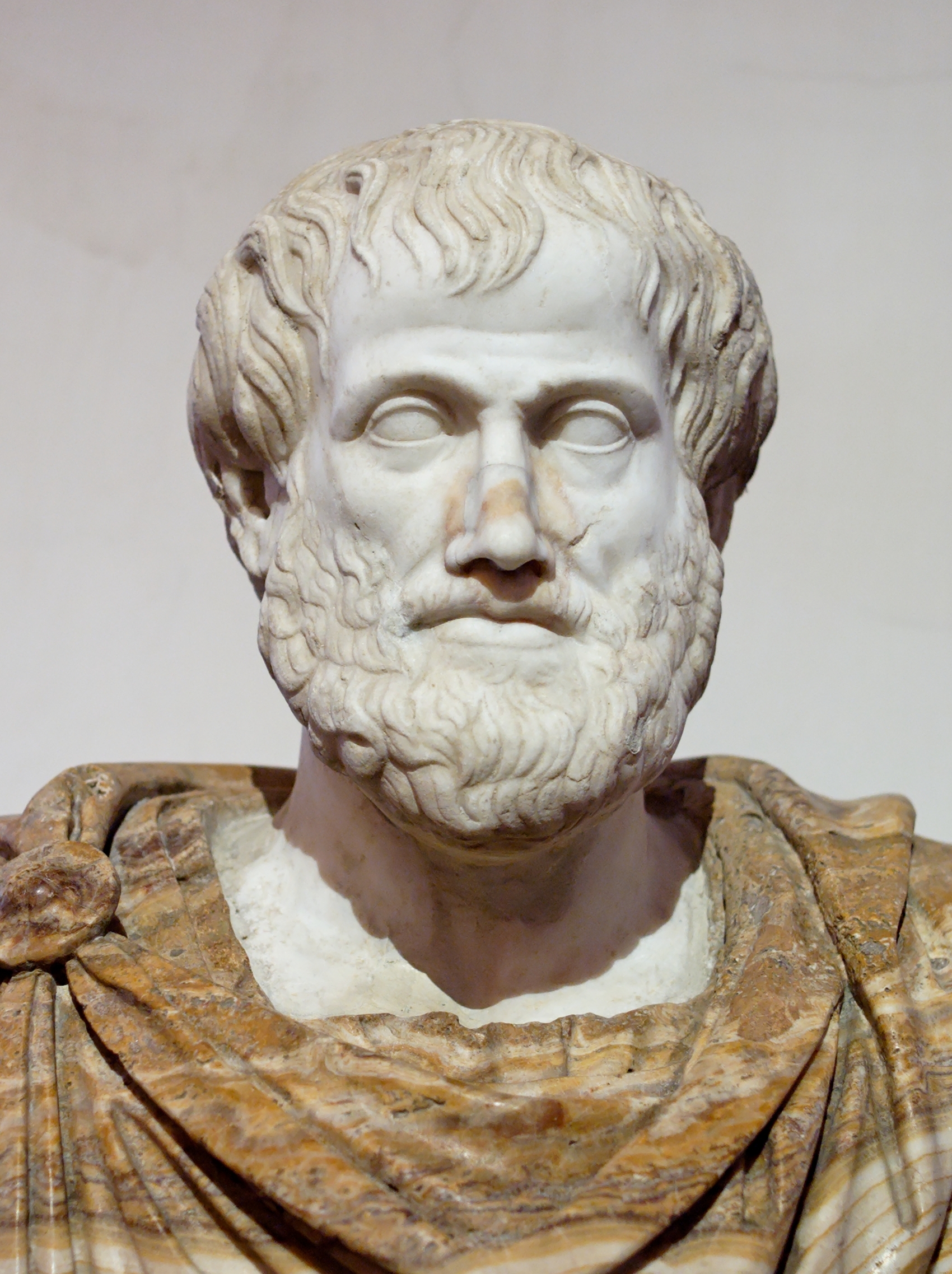

I wrote an article about it and its problems. How many people might have the skill to produce it? One very interesting thing about forgeries in general is that quality is no proof of authenticity. People often think they can identify forgeries because they are "bad." But in antiquity there were skilled artists and not so skilled ones, just as there are skilled modern artists and not so skilled ones. The sculptor Peter Rockwell has pointed out that forgeries are sometimes actually

better (in a technical sense) than original works because the forgers apply extra effort: there is

real money at stake. For example, if you look at ancient Roman portraits, the back is often less carefully worked than the front--simply because they were designed to be placed in a niche or against a wall. But in the Renaissance, when artists emulated and competed with antiquity, sculptors often very carefully finished each and every lock of hair, something ancient carvers usually did not bother to do. As for our Kouros, a skilled modern carver (or team) might have produced it. Some people believe the necessary skill could readily be found in Italy today.