Victor Saenz (Ph.D., Rice University) is Executive Director of the Houston Institute and Lecturer in the Department of Philosophy at Rice University.

What do you specialize in?

I specialize in classical philosophy, in particular the ethics of Aristotle. More broadly, I'm interested in the Aristotelian tradition as seen, for example, in Aquinas and contemporary Aristotelian philosophers. I also like thinking about contemporary ethics, the history of ethics, and the philosophy of religion.

What is a work of art that would be very helpful in understanding something about Aristotle?This feels like exactly the kind of answer you’d expect….but I’ll give it anyway. Raphael’s The School of Athens. At the center you have Plato and Aristotle, the first pointing to the heavens, the second holding his hand open, facing the earth. This is meant to illustrate a key difference between the way Plato and Aristotle understood reality. For Plato, ultimate reality was transcendent, immaterial, beautiful, and good. In contrast, the material world was constantly changing and, ultimately, something that the philosopher ought to escape and help others to escape.On the (literal) other hand, for Aristotle ordinary things, especially living things, like humans, dogs and oak trees, were a basic aspect of reality. Not only this, but in his view we can and ought to reason well about what is good for a living thing, given its nature. For humans, this means living according to our highest capacity: reason. This entails living virtues like prudence (reasoning well about action), self-control (following reason and not mere pleasure), courage (not being deterred by things like fear and pain), and justice (giving to others their due, recognizing our social nature). Importantly, that’s not to say that Aristotle denied a transcendent reality. For him, "God" (ho theos), the unmoved mover, was at the absolutely perfect, ultimate source of explanation of everything. But, importantly, to the extent that anything acts according to its nature–as humans do when they follow reason–it is approximating the perfection of the Prime Mover insofar as it is possible for it (De Anima II.4 415a25-b7). Indeed, this approximation is a form of love: the Prime Mover “produces motion by being loved” (Metaphysics Λ.7 1072b3-4). This might seem cryptic. But a not unfamiliar kind of love idolizes the beloved, seeing her as perfect, as someone we desire to make our own as deeply as we can. Or as Plato puts it, “love is wanting to possess the good forever” (Symposium, 206a). It is not within the power of mere organisms to possess the Prime Mover forever, in Aristotle's view. But the imitation of God—by acting according to our natures—is the closest we can come.

Importantly, that’s not to say that Aristotle denied a transcendent reality. For him, "God" (ho theos), the unmoved mover, was at the absolutely perfect, ultimate source of explanation of everything. But, importantly, to the extent that anything acts according to its nature–as humans do when they follow reason–it is approximating the perfection of the Prime Mover insofar as it is possible for it (De Anima II.4 415a25-b7). Indeed, this approximation is a form of love: the Prime Mover “produces motion by being loved” (Metaphysics Λ.7 1072b3-4). This might seem cryptic. But a not unfamiliar kind of love idolizes the beloved, seeing her as perfect, as someone we desire to make our own as deeply as we can. Or as Plato puts it, “love is wanting to possess the good forever” (Symposium, 206a). It is not within the power of mere organisms to possess the Prime Mover forever, in Aristotle's view. But the imitation of God—by acting according to our natures—is the closest we can come. |

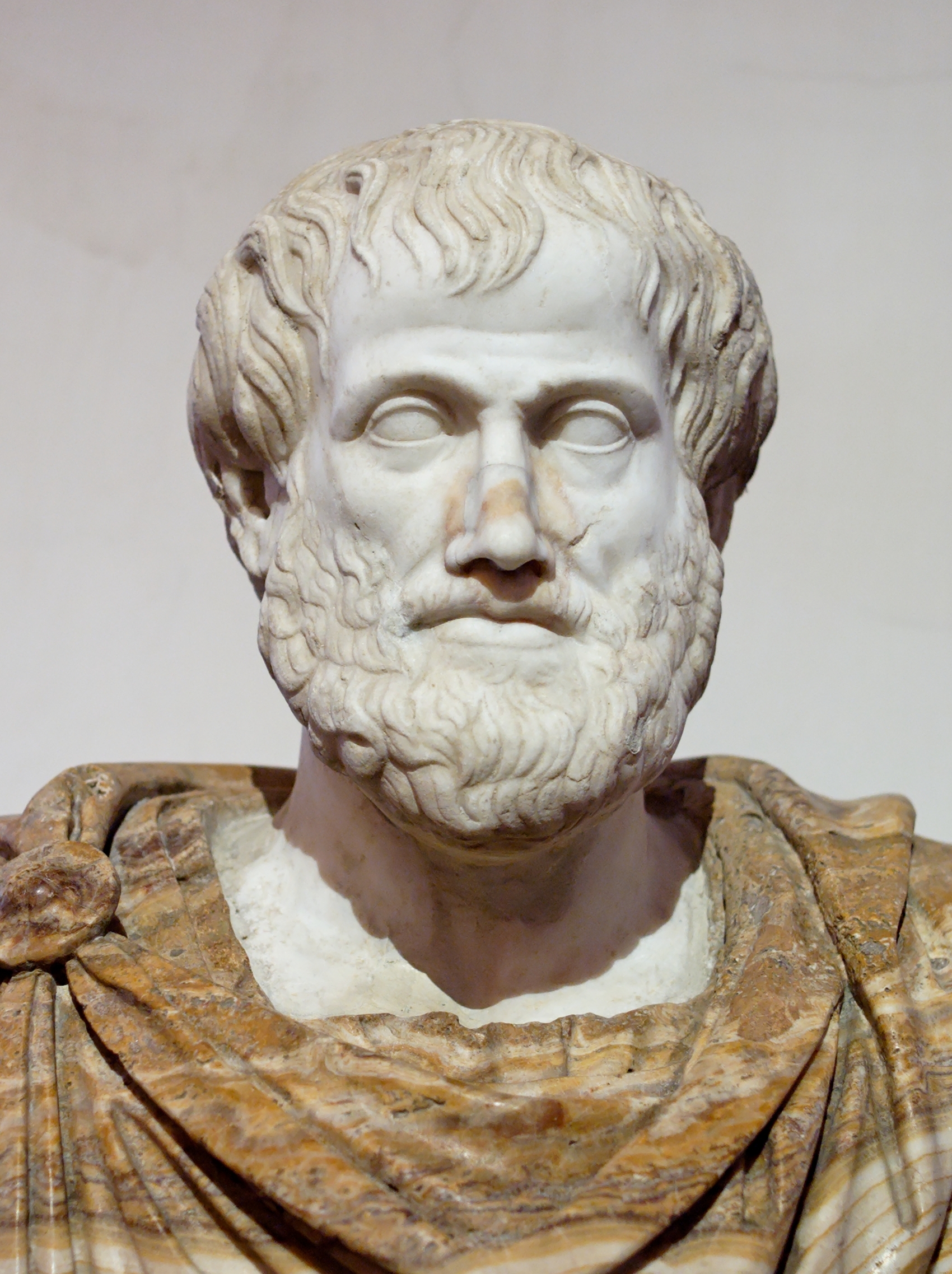

| A Hellenistic bust of Aristotle by the 4th century B.C. sculptor Lysippus from a bronze original (Palazzo Altemps, Rome) |

No comments:

Post a Comment